Mary O’Brien and Daniel McCormick photo by Monique Verdin

In 2013, fresh after planting 6,400 bald cypress and tupelo gum in the Mississippi River Delta I had a long list of what worked and what didn’t. Around that time, I wanted to make a career of planting vegetation to slow coastal land loss in the delta and was looking to collaborate.

My friend, Monique Verdin just finished a documentary film, My Louisiana Love, and was helping out at A Studio in the Woods. She told me about a chance to collaborate and put me in touch with Mary O’Brien and Daniel McCormick from San Francisco.

Daniel McCormick, Richie Blink, Monique Verdin, and Jakob Rosenwig on the mudboat, Trenasse.

Billing themselves as Watershed Sculpture, Mary and Daniel are artists who work with nature creating “sculptures that have a part in influencing the ecological balance of compromised environments.” Their work improves landscapes, gently guiding nature. I was impressed with their body of work, especially how the projects would fade into the landscape over time.

Quite the interesting couple, they met on a project in Mary’s neighborhood. The neighborhood was near an industrial area and the project centered around keeping a nearby creek flowing. Daniel came in as an architect with a background in environmental design from UC Berkeley. Mary helped organize the community around the project and got a coalition formed, Friends of the Creek. Today only two flowing creeks remain in SFO. They worked two or three years on it, and the rest is history.

In our planning conversations we discussed their influences. Daniel went to art school, served as a pilot on oceanography vessel, and had wanted to work on ecological projects. Mary said the 60s influenced them alot, as did Rachel Carson’s work. The atmosphere around the bay area too had an impact. It was clear they wanted to be a part of heading off ecological disaster.

A bit of a side note; they’re collecting their files from over the last thirty years to be curated at the Center for Art & Environment in Reno. Check back here for more photos as Mary will send more along as they gather documents.

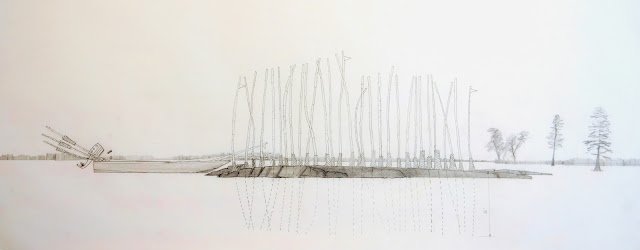

Conceptual drawing before installation, copyright Watershed Sculpture

The first spring after installation.

Nine years after installation.

Planning

The project called Lines of Defense is “An installation aimed at helping local community members of Louisiana’s Gulf Coast restore the storm surge barriers can best be described as creating a technology to help make local efforts to restore wetlands more successful.” At nearly ten years out, the project is a total success.

We focused on getting fifty trees in the ground and getting them past 18 months with minimal upkeep. Their support centered on making my tree planting efforts more efficient.

We spent a good bit of time talking about the my previous planting efforts and discussing when and where to place the installation. All this was afforded by grants and a residency at A Studio in the Woods. The struggles of getting 5,000 trees in the ground over a month were still fresh. Daniel & Mary came with a fresh set of ears and over a couple days we developed a few key efficiencies that helped make DIY restoration more successful.

Mary O’Brien shimmying the marsh scaffolding forward to plant more trees.

Tools and Tricks

Planting trees in the freshwater marshes and bottomland hardwood forests was tough. The ground is incredibly soft, so soft I was sinking to the waist in some areas. The vigorous of my previous work cost me ten pounds.

Many challenges lay ahead for the seedlings. Nutria, ravenous and intelligent, are an invasive rodent from South America brought to Louisiana in the 1930s for the fur trade. Also called Coypu, the nutria would lean on trees from past projects pushing over the protective covers to gnaw on the exposed trunks killing the newly planted trees. Learning from those observations Mary & Daniel sourced native bamboo and used it to anchor the nutria protection cages. The soil conditions were so soft we would shove the entire eighteen foot bamboo pole into the soft delta muck to anchor the cages. Solving many problems at once, they added another pole with a flag to deter errant mud boat drivers. The artists added an anti nutria sign as a garnishment to the flags.

Soft soils made installation interesting. Sinking to the knee was common. The artists developed a plywood scaffold system to distribute weight to make planting a lot easier.

Speaking of soft soils, the ground was so soft any work that happened would often lead to sinking to your waist. Mary & Daniel developed a bit of swamp scaffolding, plywood sheets leftover from a nearby construction site. We added ropes to help move them along and keep track while the tide was high. Sometimes these sheets of wood would get away from us and we would have to chase them down in the boat. The work was lighthearted and these breaks I remember fondly. Solving for success doesn’t need to be so serious.

Richie stands on marsh scaffolding, plywood scraps ripped to help distribute weight and allow of easy work on the soft soils.

Tree protectors were key for survival of the seedlings. I was using upcycled crab trap wire to save money while getting a tougher tree protector for the high energy marshes. Plastic tree wraps just weren’t holding up to the wild tidal fluctuations and occasional storm surges. I was using single stamped eighteen inch sections until this project. This allows water to pass through the cages making the guards more resilient. The artists saw the impact working the stiff wire took on my hands and created a solution using split cage made from two sections of stamped crab trap wire bent over the knee. This made planting go much faster. While doing the project we called them books. It was little things like the books and bamboo that made for easier on-the-water implementation and helped give the trees a better chance of making it long enough to survive on their own.

Tree protector made from recycled crab trap wire

These small changes greatly increased the survival rate. Even though the first year was hard on the tree we had few losses. We placed them on a spot in a high energy environment with lots of current, tides, and floating aquatic plants like hyacinth and giant salvinia which really tested our methods. Mary said, “what we’ve realized, even in restoration there is soft technology. We meld that with regional expertise and style. It’s easy and people can do it. It’s a rich experience.” Part of the process is eventually turning the projects over to the community. They’ve come to the conclusion, “We can do something as artists as long as they have local folks to partner.”

Early on, I’d visit the site to check on the trees and take time to make repairs. At first some trees took a bit of a lean due to hurricanes and abnormal water levels. I’d prop trees back up to vertical and clear cages of floating debris. At some point a boat went through the site and took out several. Today those trees would be ten feet high or better and they would stop any boat dead in the water.

Visiting the site over the years has been a pleasure. Over time, the trees grew stronger and were able to hold their own against the elements. The bamboo flags began to fall and true to Mary and Daniel’s philosophy, the artists’ presence began to fade. If you didn’t know better, you may think this strong stand of cypress was a caprice of nature, a fluke.

February 2021 view from gulf side with Targa Resources behind the installation. When reaching out to plant officials by email during the project, I never received any follow up. An investment then of several thousand trees would have undoubtedly reduced wave heights and potential damage to their facility from future hurricanes.

The project is a testament of humanity gently guiding nature for positive outcomes. Many times, we can restore what’s been lost. This work is scalable and needs to be considered for massive, yet dialed in implementation.

Crossing disciplines is key to realizing that there is no box. Our imaginations must flow like water to solve for the survival of our species, and we can only do it together.

Nature-based solutions are key to making it as far as we can into the climate crisis. Unlikely methods, like crossing disciplines, will help provide answers and find efficiencies when dealing with the tough environmental problems we’re facing. We need everyone’s help. We must not silo ourselves into disciplines, rather share the load and be open to new ideas and concepts in order to survive.

Three years after planting.

While the peninsula we saved was small, the lessons were important and I’m glad to offer them here for interested folks. Just as we can gently guide nature to help humanity, we must be willing to learn to adapt with the environments we inhabit. Working together is key to this.

I’d like to thank Mary O’Brien and Daniel McCormick, Cammie and the staff at A Studio in the Woods, Monique Verdin, Jacob Rosenzweig, and Alex Treadaway for helping to make this project possible. I’m excited for the next collaboration.

-Richie

Lines of Defense February 22, 2021