Baby Delta

Sometime around the turn of the last century, a small cut, or crevasse opened up along the bank of Pass a Loutre, the easternmost pass of the Mississippi River Delta. A few different stories tell talk of its birth. Some folks said a competing oyster farmer looking to impact competition, some said it was a trapper’s shortcut gone wild, and still other accounts say that it was just the river doing river things.

What happened next is incredible. Over thirty years, a ten thousand acre delta rose from the bottom of Garden Island Bay, a large embayment between South and Southeast Passes. This new delta, a vast complex of passes, bays, lagoons, and ponds, became public land. Today, this quadrant of the birdfoot delta still bears the name from which this new wetland arose.

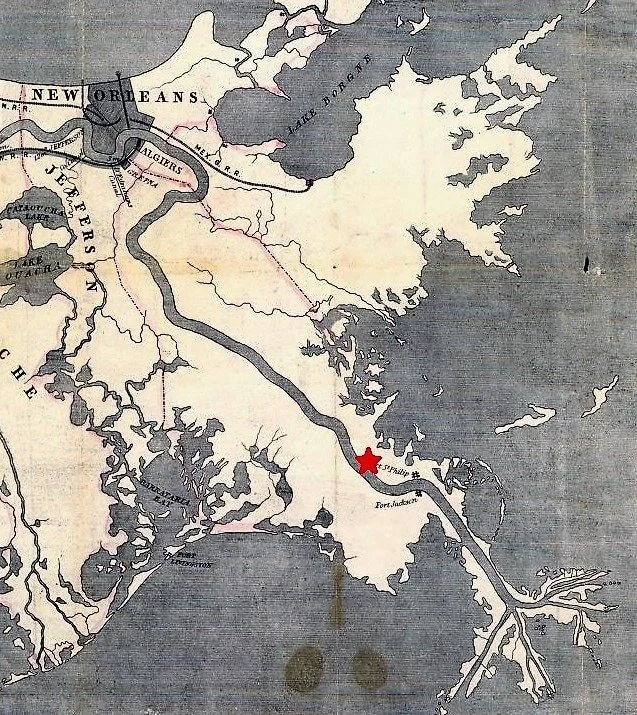

1862 nautical chart of Garden Island Bay

Conservation and Public Access

On Nov. 1, 1921 the State of Louisiana christened this baby delta the Pass a Loutre Wildlife Management Area, making it Louisiana’s first in state. The WMA is a 115,000 acre intertidal wetland area available for birding, fishing, duck hunting, and camping. Today, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries manages 1.6 million acres of public lands and waterways.

Recently, the WMA celebrated its hundredth anniversary. While the habitat is still prime, the long term outlook is bleak for the current form or ponds and passes. Deltas naturally shift overtime and the modern bird foot delta is bound by the laws of the universe to shift before being reborn in another form elsewhere on the coast. Sometime in the next hundred years this area will be a shoal, lined with some barrier island-like features.

2012 image of the new delta complex at Garden Island Bay

Getting Creative

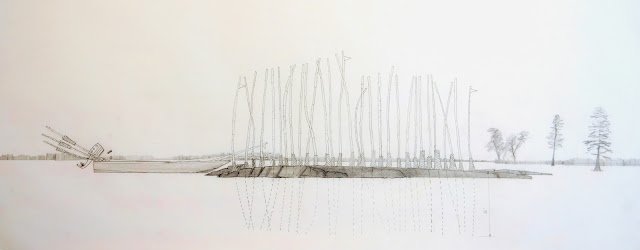

Since Pass a Loutre is a long way down river, it may be best to spend a night to really absorb this watery landscape. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries built five campgrounds to help campers find some dry land to set up camp. These safe havens in the remote delta were creatively built on the spoil banks of human built crevasses, that were intentionally dug to help along the delta building process. This work has been ongoing since at least the 1980s in this part of the delta and has created at least a thousand acres of wetlands since construction.

These well placed crevasses provide freshwater and ample sediment supply to keep this rapidly sinking habitat for many species above the surface. Doing more than one thing at a time, with little funding within government is difficult, hats off to the department and staff for thinking in these creative ways. In 2020 these campgrounds were rebuilt using Deepwater Horizon fines for loss of recreational use.

A crevasse digging machine.

Camping

Everyone has their own style of camping. This video of a group enjoying themselves down on the refuge at the campgrounds. They’ve got an impressive set-up, but you can have just as much fun with a simpler spread.

There’s something to be said about getting over the horizon and spending a night under the stars in silence. Hunters and anglers living in Louisiana should make a trip down to the delta at least once to experience a place that will not be around forever.

To get the most from your visit, having a plan is crucial to safely enjoying the Pass a Loutre WMA. Here is a list of the basics to be comfortable and legal camping downriver.

Float plan - Share this with someone you know, I keep some filled out with my boat information already entered ahead of time. Maybe leave a printed copy on the dash of your vehicle.

Tent

Firewood

Extra clothes

Bug spray

Garbage bags -pack out what you pack in.

Check the weather and pack for the occasion

A buddy boat - The WMA is over the horizon and cell phone service is limited at best.

Self Clearing permit. These are important and help LDWF staff better understand how folks are using the WMA.

Camping permits are $7 nightly for up to five adults.

A Wild Louisiana Stamp

Now we can take a look at these remote campgrounds!

Dredging efforts near the Freshwater Reservoir campground. The sediment is being dredged from South Pass and the campground is back to normal today.

Cadro Pass Campground at Freshwater Reservoir ‘ 29°05.4546′ N~89° 12.6540’ W

This campground is situated next to a dredge spoil and has the most amount of dry ground. When South Pass was last dredged, the spoils were placed adjacent to the campground allowing for access to rare upland habitat down in the Birdfoot’s Foot Delta. Be sure to stay off any vegetation trying to get a foothold on the loose sand. Coyote, and rabbit are present, as are the everpresent wild hogs.

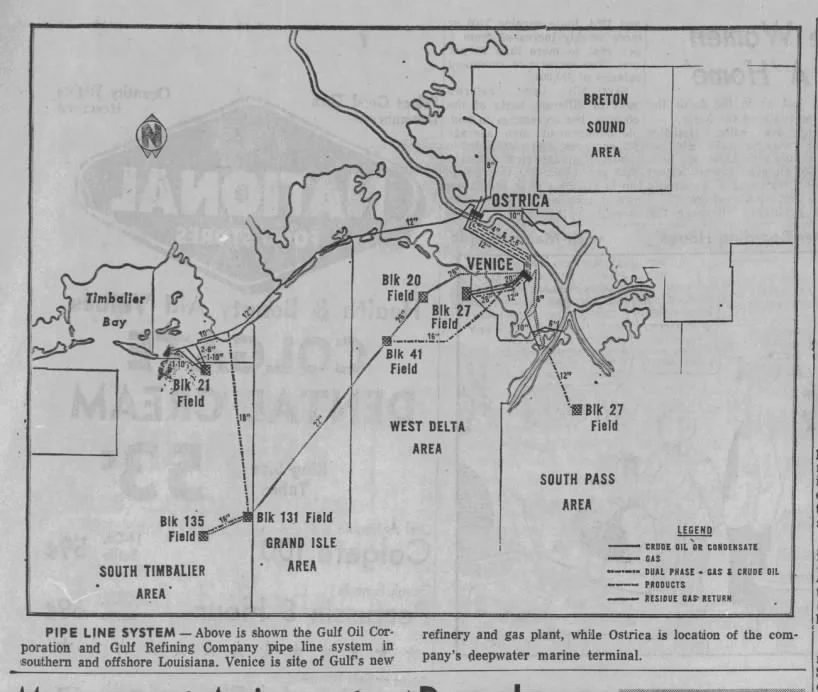

Chart of sulphur mining operations

The reservoir was part of a sulphur mining operation within the WMA that began production in 1953. The large facility, located across Denis Pass from the campground. The removal of the sulphur mine and associated infrastructure was very carefully carried out. Today, one cannot tell from the water’s edge where the operation once was located.

Loomis #1

Loomis #1 Campground ‘ 29°07.6908′ N~89°11.5794’ W

This campground has the largest dock of the group and can host a flotilla of mud boats. Fire rings and barbeque pits can be found at this one too.

Loomis #2

Loomis No. 2 Campground ‘ 29° 07.3806′ N~89° 10.7220’ W

Loomis #2 is the more remote campground of the bunch with many twists and turns to get there. It’s also the smallest. This spot is a bit exposed and may be harder spot to camp in higher winds.

South Pass Campground

South Pass Campground ’ 29° 06.3204′ N~89°14.0562′ W

South Pass has a big space available for tent camping. This is a popular spot with duck hunters and maybe the closest to Venice. It’s easy to get too right off South Pass and a welcome stop for folks paddling the length of the Mississippi River. Lots of picnic tables and fire rings are available.

Southeast Pass Campground

Southeast Pass ‘ 29° 08.3418 N~89° 08.9220’ W

This spot is the furthest of the campgrounds from Venice. It has all the same amenities as the other campgrounds.

With a little planning, an overnight at the Pass a Loutre Wildlife Management Area can be a once in a lifetime experience. We hope you enjoy your visit.