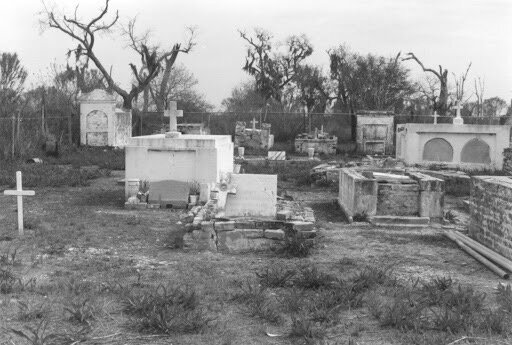

Point Pleasant Cemetery, across the Mississippi River from Empire, Louisiana. Courtesy Findagrave.com

One of my first jobs was running cattle under the guidance of Captain Phillip Simmons. The east side of the Mississippi River, across from Empire, Louisiana, where I grew up, is unoccupied by people. Its tough country, a land ruled by nature. The ground is incredibly low and soft. Four-wheelers and horses can only cover the higher territory or else they sink and become a burden on the operation. Men on foot were needed to drive the cattle from the marsh to the ridges and levees for inoculation and shipping to market. The cattle would make these shifts in clear patterns. Each herd had its own personality. After awhile the job became predictable and gave me the time to get to known the other rustlers, mostly shrimpers during the slow season.

Around 1200 head of cattle live on the East side of the Mississippi River from Bohemia to Venice.

I was on one of these cattle herding trips the first time I went to the Point Pleasant Cemetery. It was nearly dark and I was with Capt. Phil in a flatboat headed to pick up the cattle crew at the end of the day. We eased into a tight ditch with tea colored water. The small cut was too narrow for the boat to turn around. At the end of the dead end canal, just past some decrepit oak trees was the graveyard. Live oak, spanish moss, and palmetto occupied a small mound, what I found to be the older section of the graveyard, beyond that were the newer graves. As we pulled in a couple crows took off. The hair on the back of my neck stood up.

Everyday tides put water into the Point Pleasant Cemetery

Beyond the canal bank, hand dug by homesteaders sometime in the mid 1800s, were tombs in various states of decay. Most from the 1830s through the 1910s. Oddly enough one looked nearly brand new. The tomb’s owner having occupied it in the mid 1970s. The facade well-kept by my captain that evening, a caring nephew. At the time I had no idea the little cemetery even existed. The place gave me the creeps.

Captain Phillip Simmons during the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in 2010. the Ostrica Locks were fully opened to flush oil from the marshes.

Captain Phil shared a story with me about a man that refused to be buried in the cemetery. During a yellow fever epidemic, the man’s wife and young daughter died in short succession. He built an elaborate and sturdy tomb and mourned daily after working the oyster reefs. During a particularly bad hurricane in 1919, the well built, and water tight tomb floated off and wasn’t found. After a futile search the man said, “To hell with this place, bury me on the high land.”

Around that time, a new canal had just been dug connecting Bay Adams and Grand Bayou on the west side of the Mississippi River with steam shovels. The spoil banks were nearly thirty feet high. A few years later that’s where the man was buried.

Only a channel marker and oyster poles delineating leased water bottoms suggest where that canal bank existed. Extreme land loss, caused by canal digging and levees, claimed that marsh years ago.

The Woodmen of the World Fraternity would cover burial cost for members and their family. Not many harvestable trees are in the area any longer. This petrified wood stump likely traveled by steamboat to Point Pleasant.

While in better shape than the lost land across the river, today the cemetery can hardly handle high tide without a few inches of water covering the ground. Low spots are permanently submerged. Cattle haphazardly graze through the tombs, clumsily knocking the markers around in the soft deltaic soils. Its a place largely forgotten save for a few hunters and Capt. Phil’s family and friends.

Point Pleasant Cemetery in 2019.

Over the years, Capt. Phil shared much oral history of the area with me. As we would pass various landmarks, some as simple as a lone live oak tree or old cattle bridge, he shared the last names of the homesteaders, their specialty, or how they were related to him. Names like Johnson and Cosse were common. With a little imagination, you could almost picture the neatly kept homes with West Indies style roofs, and long piers into the river awaiting weekly packet boats with names like El Rito and New Majestic.

Russell Lee 1938

Those boats would bring mail, household goods, and elixirs ordered from Sears catalogs. On the return trip to New Orleans cattle, oysters, and citrus fruit were headed upstream. There were rows of orange trees, thoughtfully mended cattle pens, and piles of bleached oyster shells scattered across the landscape. Often his stories would highlight practical ways people adapted to life in the delta and how self determination, ingenuity, and a positive attitude allowed the people to lead an easier life.

A young man inspects the citrus crop. Plaquemines Parish is know for the once bountiful citrus harvests. Arthur Rothstein 1935, Courtesy Library of Congress

It was a simple and tough life, but an honest one. It was turned upside down after the great flood of 1927, which kicked off major flood control improvements all along the Mississippi River Valley. The communities and homesteads from Bohemia to Ostrica were forced from their homes and land. This created much tension that split families apart. The creation of the Bohemia Spillway, a pressure relief valve lauded to save the city of New Orleans from flooding was needed for the greater good. Some folks literally took their homes apart board by board and reconstructed them across the river in Empire, Louisiana. This land was viewed as subpar in both elevation and quality for farming. Other folks left the state entirely, disenfranchised, looking to start fresh elsewhere. It took more than 60 years before the courts decided the dependents should be compensated for the loss. Today you can find land owners as far as Detroit and Atlanta paying $6 annual property tax for a splintered percentage interest in a plot within the spillway.

Arthur Rothstein 1935, courtesy Library of Congress

Looking at the landscape can be equal parts looking into the future as the past. The Bohemia Spillway shows how areas of Louisiana will look after the people leave. Not much is left of those old home sites. Only some bricks, rusted farm implements, and bottle shards remain.

Left behind ground aerator.

A six foot potato ridge levee separates the river from the back marshes which are not nearly as firm and dry as 20 years ago. The old remnant levee is doing more harm than good at this point, choking off what could be an annual replenishment of sediment across the landscape.

From Pencil Points, April 1938

Those levees the early settlers helped to maintained still hold back river water below Bayou Lamoque, just downstream from the official ending of the Bohemia Spillway. The area north of the Bayou Lamoque, and south of Pointe a la Hache, had the levee degraded by bulldozers for the actual spillway. That ground is several feet higher today due to that annual overtopping of the natural levees in spring floods.

The older Bayou Lamoque Diversion built in the 1950s, The newer structure is similar with construction completed in the 1970s. Note the cattle in the bottom right of the photo.

The new sediment deposited in the Bohemia Spillway outpaces the natural sinking of the delta making this the only geography in Plaquemines Parish where the land is getting higher over the years. Black willow grow along the river and renewed distributaries. Large live oaks extend nearly all the way to the back levee ditch. Six feet of elevation is common nearer to the river, and those areas are dry most of the year. The understory is clean and largely free of invasive species. Deer abound in the active spillway. In contrast, the area below the spillway, delineated by Bayou Lamoque downstream, is dominated by Chinese tallow trees and soft, low marshes.

The batture of the Bohemia Spillway is overtopped annually during spring floods.

The land went back to nature in the most complete way. The Bohemia Spillway is about as close as you can see to what things were like before the Europeans arrived in the Mississippi River Delta. Now with Mardi Gras Pass digging in, back bays are being converted to flats and then marshes. The cycle of building land continues.

Uhlan Bay, near Mardi Gras Pass, with new flats breaking the surface.

On our trips you can see these special places for yourself and hear the stories of how they were occupied, abandoned, and what could be. Come see what the future holds just downstream.

-Richie