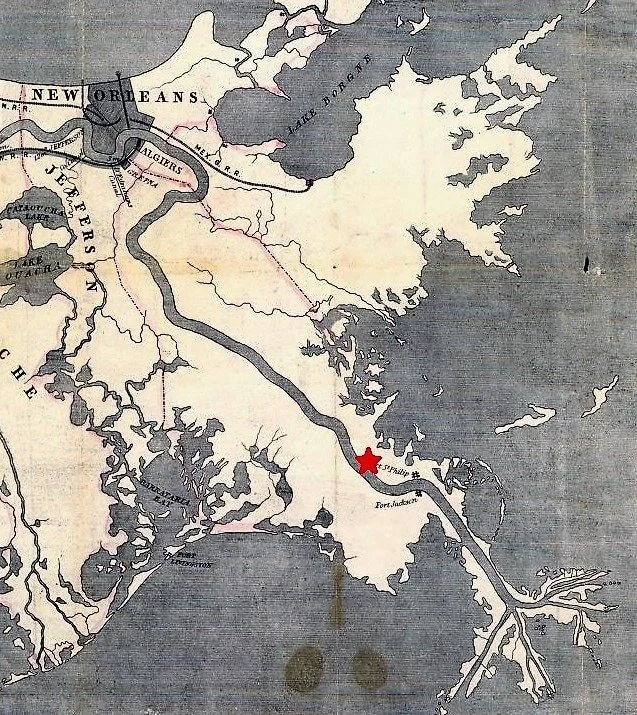

1853 map of with the location of Quarantine Station. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The site of the Ostrica, Louisiana has a storied history. Situated 75 miles downstream of New Orleans just across the Mississippi River from the current settlement of Buras, Louisiana, the area has served as a quarantine station, and oyster cannery, and the site of a series of navigation locks that served for more than a century.

In 1855 a quarantine station was established. Abandoned by the 1860s, the station had several large buildings and a staff. This was set up to make sure ships were disease free before making their way to the city.

In 1857 a French naval vessel, the Tonnerre, stopped to seek shelter. During its journey at sea, and stay at the quarantine station, more than 30 sailors died. The sailors were buried in the cemetery nearby, the location of which seems to be lost to history. In 1917, the deceased crew members of the Tonnerre were meticulously disinterred and relocated, along with a stone obelisk, to the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans’ French Quarter. You can read more about that history here.

Tonnerre, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Sometime in the 19th century, an encampment of Yugoslavian immigrants settled in the area of Quarantine Bay adjacent to Ostrica in single, one room camps. These were built in support of oyster cultivation that was being pioneered at the time.

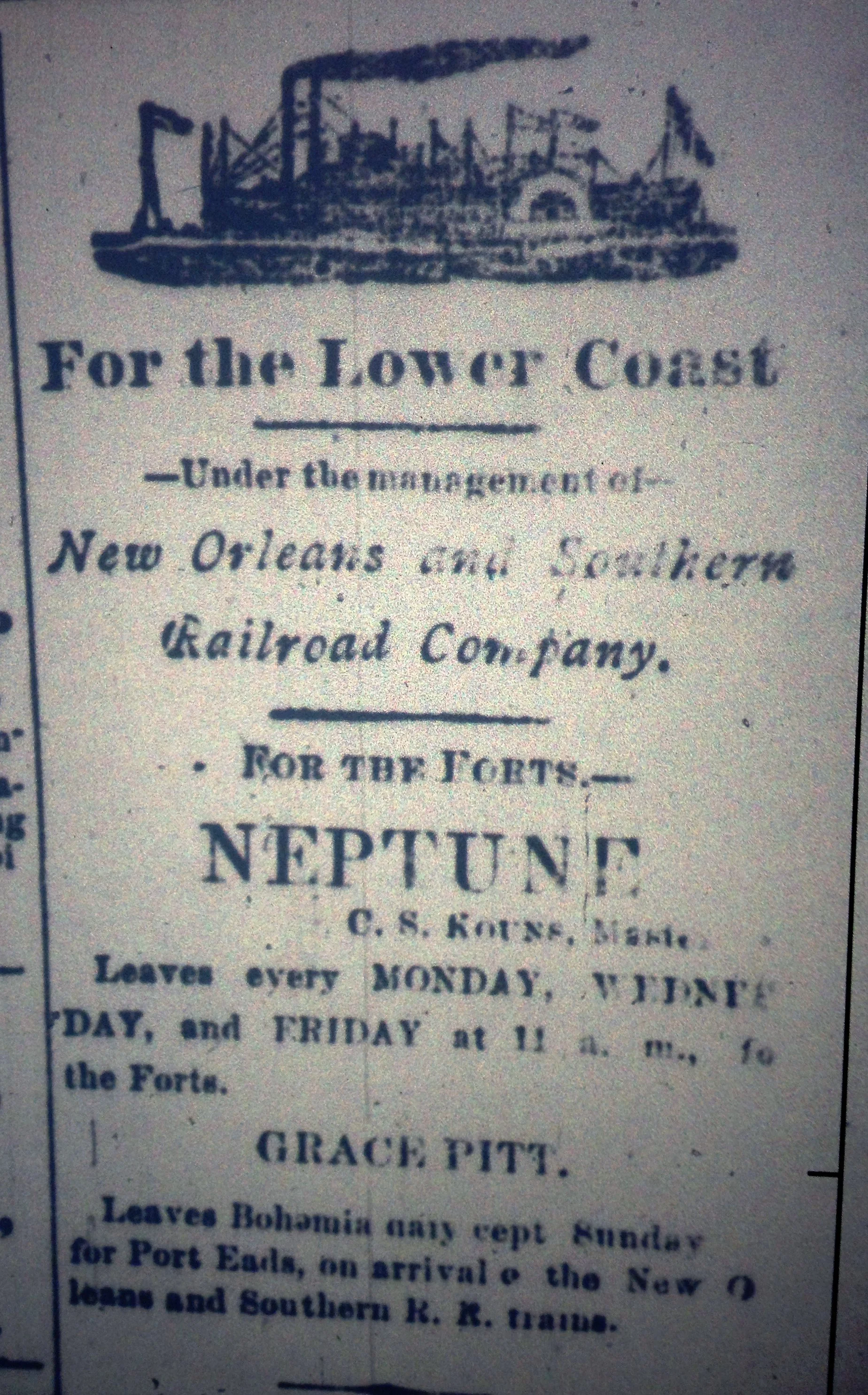

In the 1880s, a set of locks was constructed at Ostrica. This water access route provided reliable and efficient means to navigate from back bays directly into the Mississippi River and speeded the transport of the perishable cargo.

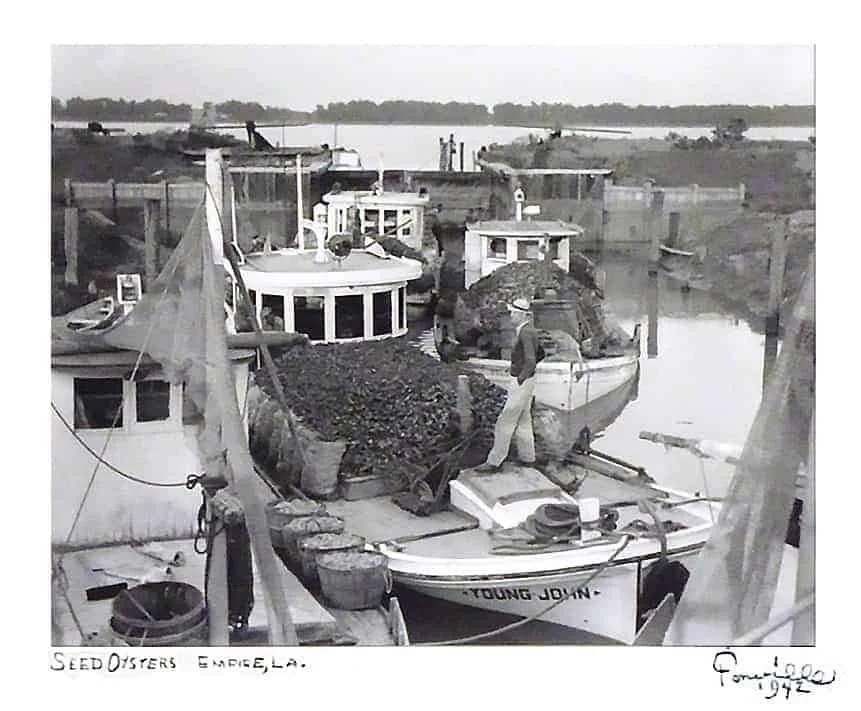

Photo of adjacent Empire Locks by Fonville Winans. This lock with wooden gates and earthen walls was similar to the original lock structures at Ostrica.

Milos M. Vujnovich sums up the need for he Ostrica Locks in his 1974 book Yugoslavs In Louisiana:

Before the opening of The Empire and the Ostrica Locks during the early 1900s, this was lone by a long, indirect, and tedious route. They would load the boats with the seed oysters from the public reefs on the east side of the river. During the months when the river level was high, they would enter the Mississippi at the Baptiste Collette Bayou (about five miles below Olga), cross the river and at the Jump, near Venice, enter the Grand Pass and go southward to the Gulf of Mexico then turn in a northwesterly direction, enter the Bastian Bay at Grand Bayou Pass, cross the Bastian Bay and proceed to Bayou Cook, Bayou Le Chutte, Ferrand Bay, Ferrand Bayou, or Adams Bay, transfer the oysters to a smaller skiff, and bed them. The smaller boats, which could not dare the open seas, usually followed this route.

Photo by Fonville Winans. Tonging and bedding oysters was common at Ostrica. This photo was taken south of Morgan City.

Eventually an oyster cannery was built to service nearby reefs. Over time a surrounding village coalesced at Ostrica, which is the Croatian word for oyster.

Carolyn Ramsey writes in her 1957 book, Cajuns on the Bayou about the spartan quarters built by folks gaining a foothold in the United States while visiting via packet boat.

This narrow man-made canal… “Mostly dug by Cap'n Pete [Zibilich] hisself”… was a straight blue-grey shaft through the tall weaving draperies of marsh grass that surrounded us on either side. Down it the little lugger traveled smoothly, taking us out of the world of the oyster settlement and into the great flat prairies of grass, water and skies that stretched far and wide around and above us. There was an immensity to this landscape that took away the need for speech.

A modest oyster cannery was located nearby the Ostrica Lock which inspired its namesake.

We rode silently together until we sighted a tiny hut far out upon the sea of marsh grass. As we came nearer I saw that it stood on spindly wooden legs like stilts, six feet above ground.

Surrounding it and beneath it was a blanket of oyster shells, gleaming white and clean in the late sun's rays. No sprig of grass, no flowers, no unfunctional thing. Narrow, wobbly steps led up to the single room. Draped over them at the top was a throw net and leaning against the house were push poles, a boat anchor, a large coil of rope, several pairs of oyster tongs. Tied to one of the house piers were two skiffs, oars stacked neatly inside.

Prior to the construction of the locks at Ostrica, oyster growers relied on packet boats that would work a rotation between New Orleans and smaller coastal settlements.

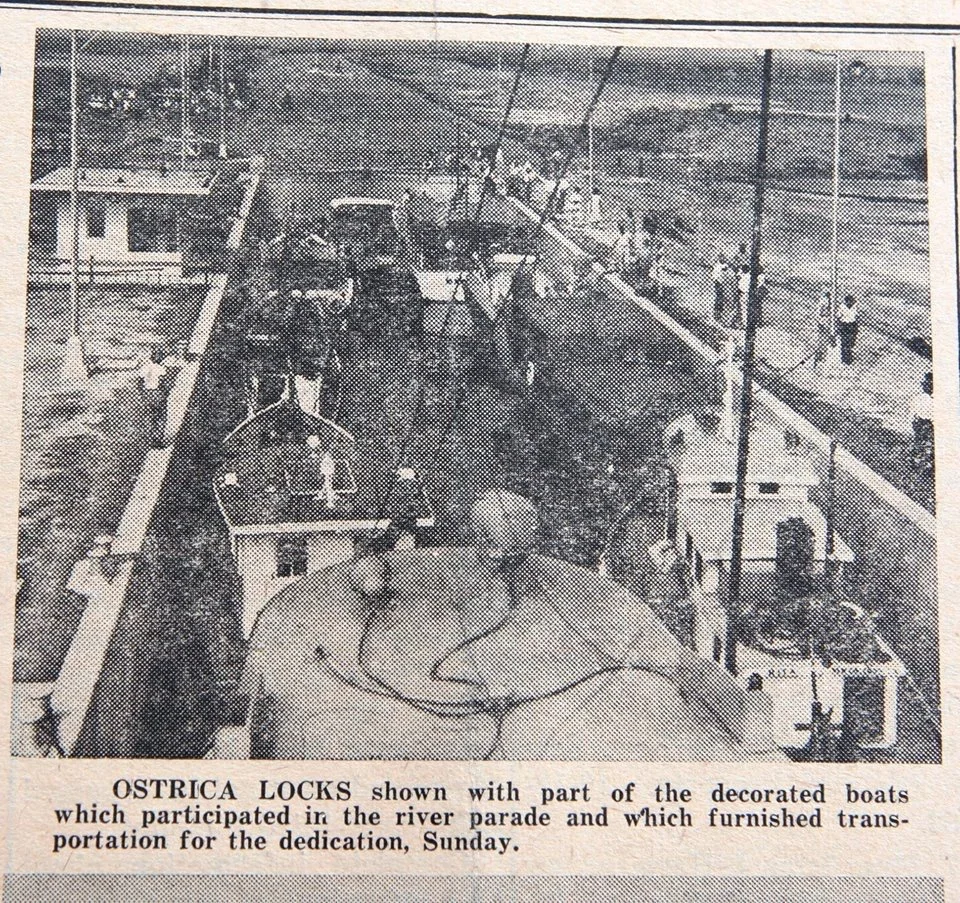

In 1953 a modern iteration of the Ostrica Lock was constructed as oil and gas exploration expanded in the area. Oyster cultivation was modernized around the same time taking advantage of advancements in hydraulics and management techniques for wild reef productivity. This new lock had concrete walls and steel gates.

The modern iteration of the Ostrica Lock during the 1953 construction.

Newspaper clipping from the opening of the 1953 iteration of the Ostrica Lock.

Courtesy of the American Canal Society

Ostrica soon became an important hub for oil and gas development in Louisiana. The abundant oil reserves within Quarantine Bay and deepwater access of the Mississippi River created the right ingredients for a burgeoning industry.

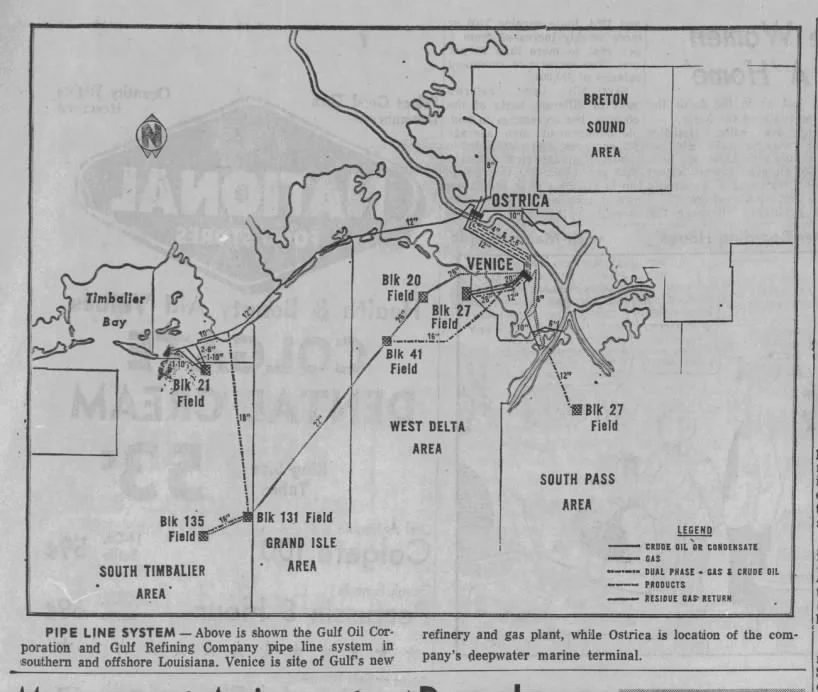

Gulf Oil Company drilled many wells and created an oil shipping depot on the banks of the Mississippi. The company installed compressors and gathering stations to lift and process crude oil before shipping it via barge to refineries upstream. As oil and gas drilling and production ventured further offshore, a pipeline network became more advanced. Eventually a 104 mile long pipeline was built to directly connect the nearby terminal to a refinery in Pascagoula, Ms.

These facilities became modernized over the years. Today Ostrica is home to the Chevron Empire Terminal, which is capable of landing tankers of at least 750’.

Eagle Hanover loading at the Chevron Empire Terminal. Photo by author.

Hurricane Katrina caused great devastation to the area in 2005. The lock was in a state of disrepair and out of service for years after the storm. To facilitate navigation, the lock was left wide open for several years for during repairs to the lock keeper’s quarters and support buildings. After repairs, the lock was brought back into service for about a decade.

In 2010 there was much uncertainty during the 87 day long Deepwater Horizon spill. Locals and resource managers were grasping for ways to blunt the ecological impacts from the massive amounts of crude oil floating in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the tactics to prevent oil slicks from reaching interior marshes was utilizing existing diversions and the Ostrica Locks to create a hydrological head. To do this, the lock operations regiment was reversed. Instead of a constant state of closure, with each gate opening to step down boats from the level of the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, the lock gates were both opened to allow for large amounts of water to inundate adjacent wetlands and prevent any oil slicks from entering sensitive marshes. This move upset some fishing operators.

Captain Phillip Simmons, a cattle rancher, during the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in 2010. The background of this image looks drastically different today with many willows nearing 30’.

In 2004 a small cut began to develop just downstream of the locks. That cut, which locals simply call Ostrica Cut, is today a navigable waterway. In 2019, the development of Neptune Pass created a new large channel making the locks obsolete.

How we think about infrastructure, its use and reuse, is going to be key in how we deal with blunting the impacts of a changing climate. In the future, it may be possible to utilize the lock chamber as a sediment diversion, or for other water control uses. The health of a large wetland area upstream of the lock could be managed with this structure. Ostrica has had a long and varied history, its future can be just as interesting and productive.

-Richie